Decoder Index

The internet’s physical layer, in plain language and comparative terms.

How to read the cable map and avoid confusing it with ships or planes.

Fiber optics, repeaters, power feed, and route engineering.

Why milliseconds reshape trading, gaming, and cloud performance.

Where cables converge, and why geography becomes leverage.

The real causes of outages and the logistics of fixing glass on the seabed.

Why satellites are critical—but not the backbone replacement people imagine.

Search-friendly answers and definitions (high-intent keywords).

Executive Summary: The Physical Internet, Not the Myth

People say “the cloud” as if data floats. In reality, global connectivity is a set of physical routes—especially submarine fiber optic cables—that behave like railroads for photons: fixed corridors, finite capacity, measurable delays, and strategic choke points.

This page is intentionally comparative because that is what search engines reward: clear definitions, structured sections, and practical takeaways. We answer the questions people actually type: What are submarine cables? How do undersea internet cables work? Where are the internet chokepoints? Why does latency matter? What happens when a cable breaks?

Use this briefing inside The World Pulse Game as your “pattern recognition cheat code.” When labels are removed, you will still be able to identify the internet backbone map by its signature: dense coast-hugging arcs, high concentration at a few landing corridors, and continental stitching that ignores airports and ports.

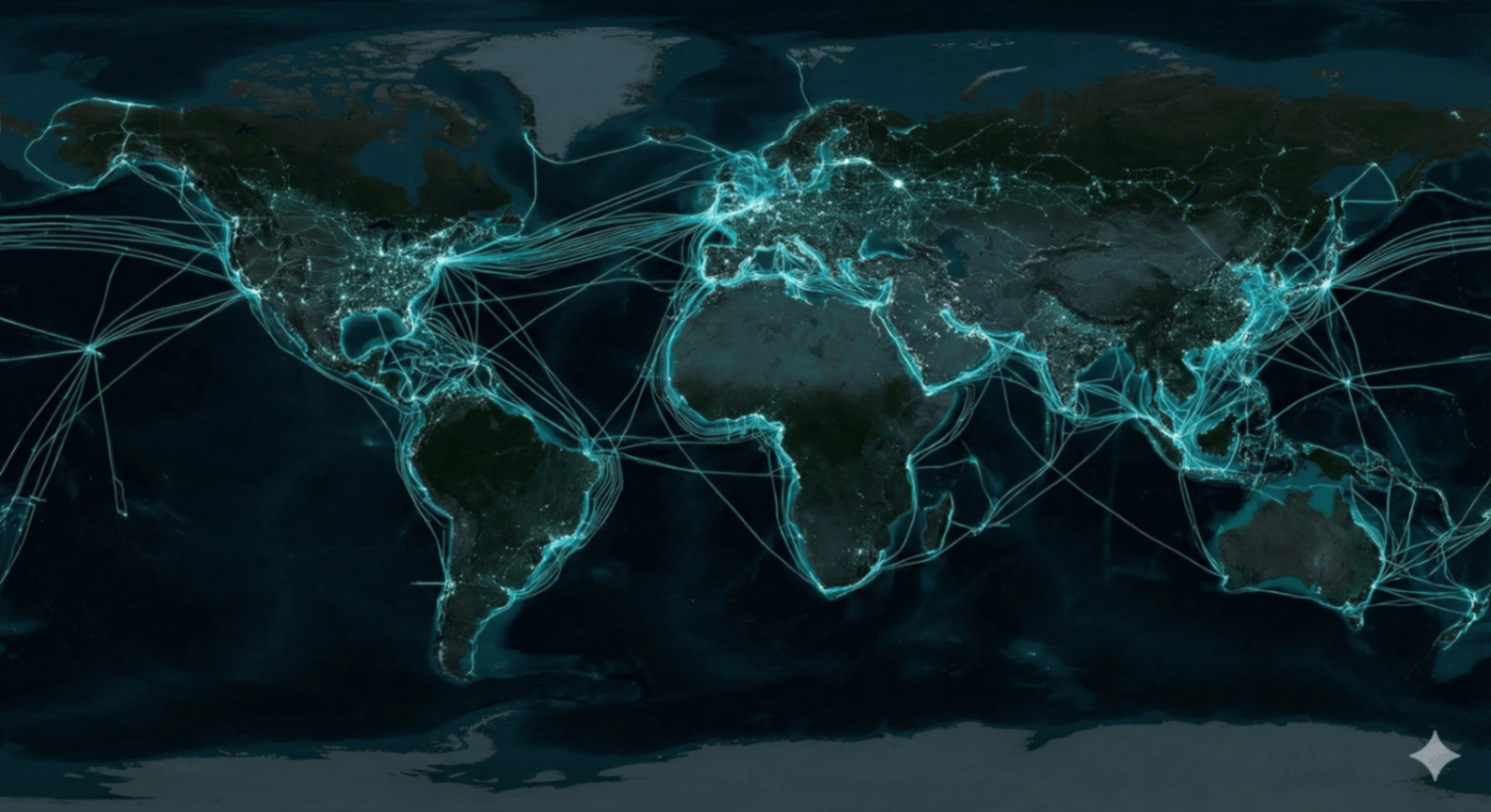

The Internet Has a Shape

The map above is the internet’s skeleton. It is not a coverage map (that would show circles and gradients like cellular coverage). It is not a mobility map (that would show flows like shipping lanes and flight paths). A submarine cable map is a topology map: it shows the physical corridors where bandwidth is concentrated, and where failures are most disruptive.

The Three Visual Tells

- Landing density: cables stack near specific coasts and urban regions, then branch inland through terrestrial fiber.

- Ocean behavior: cables do not “wander” like ships; they aim for shortest feasible seafloor routes with engineered detours around hazards.

- Connector logic: cables connect data centers and economies, not tourist destinations; the pattern is “value routing,” not “human travel.”

In the World Pulse sequence, the most common mistake is calling this “shipping routes.” That confusion is productive: it forces you to think about the difference between moving atoms and moving bits. Shipping lanes are constrained by ports, canals, and fuel economics; cable routes are constrained by landing stations, seabed risk, and latency economics. One moves containers; the other moves decisions.

Technical Readout: How Undersea Internet Cables Work

Submarine cables are engineered for a brutal environment: pressure, corrosion, fishing gear, and long distances without human access. Yet their core is simple: send light pulses through glass, amplify them along the way, and route the traffic at landing stations. The complexity is in the constraints—distance, repairability, and risk concentration.

What’s inside the “garden hose”

- Core: hair-thin glass fibers carrying light (data).

- Strength: steel armoring (more armoring near coasts).

- Power: conductive elements feeding repeaters.

- Sealing: waterproof layers and insulation for decades of exposure.

Practical distinction: deep-ocean segments are often lightly armored; shallow-water segments are heavily armored because that’s where most damage occurs.

Photons, wavelengths, and capacity

Capacity scales by running multiple wavelengths through the same fiber (think: many colors of light). Modern systems also pair multiple fiber pairs and upgrade terminal equipment over time to push more bits through the same route.

Why it matters for SEO queries like “internet capacity” and “bandwidth routes”: the map is not only geography—it’s throughput and upgrade potential.

Amplifying the signal across oceans

Light attenuates. Over long distances, undersea cables rely on repeater units spaced along the route to keep signals readable. Those repeaters need reliable power delivery and must operate for years without physical access.

Why cables don’t always go “straight”

The shortest line is not always the best line. Routes avoid steep slopes, unstable seabed, heavy trawling zones, and politically risky coastlines. Landing station access, permitting, and maintenance fleets also shape where lines can realistically go.

Map-reading tip: cables “bend” where risk, regulation, and seabed reality override pure geometry.

Latency & The Economics of Time

Search intent reality: people don’t only ask “what is a submarine cable.” They ask why latency matters. Latency is the time it takes for data to travel from A to B. It affects everything that depends on responsiveness: online gaming, video calls, cloud apps, remote work, financial trading, and even “how fast a website feels.”

Undersea cables win because they provide direct, high-capacity corridors. Even though light moves slower in glass than in vacuum, the route is often more direct and far more scalable per delivered bit than orbit-based links. That is why the internet backbone remains a “glass ocean,” while satellites specialize in reach and redundancy.

Milliseconds become money

Faster routes can improve execution timing. That incentive funds “shorter cable projects” and optimized terrestrial paths between landing stations and exchanges.

User experience is distance

When data centers are closer—logically and physically—apps feel instant. Undersea links determine which regions can be served with low delay.

Stability beats peak speed

Jitter and routing detours matter. Cable outages can force traffic onto longer paths, creating sudden lag spikes even when “internet speed” looks fine.

Bandwidth is capacity. Latency is distance. The cable map is where those two become geography.

Chokepoints & Landing Stations

The internet backbone is not evenly distributed. It concentrates where continents pinch, where coasts are stable, and where infrastructure already exists.

What is a chokepoint?

A chokepoint is a constrained corridor where many routes converge because there are limited alternatives: narrow seas, specific coastal landfalls, or politically feasible landing areas. Chokepoints amplify risk because a localized incident can have non-local effects.

- Coastal geography and shallow-water constraints

- Permitting, regulation, and landing availability

- Existing terrestrial fiber corridors and data centers

- Seabed hazards and navigational safety

What is a landing station?

Landing stations are the “ports” of the digital ocean: secure coastal facilities where cables transition from underwater fiber to terrestrial networks. They concentrate routing equipment, power feed, and interconnection services—making them both valuable and sensitive.

Comparative Recognition: Cables vs Shipping vs Aviation

Use in World PulseFixed topology lines, concentrated at landing stations, shaped by seabed risk and latency.

Broad corridors between ports, visible choke points at canals/straits, influenced by trade patterns.

Dense over land hubs, strong transoceanic arcs, daily rhythm shifts with time zones.

Risk, Breaks, and Repair: The Operational Reality

People imagine “hacking the internet” as software. But at the backbone level, disruption is often physical: a cable is cut, degraded, or temporarily unavailable. The most frequent causes are mundane—anchors and fishing gear—because most human activity happens where the cables must pass: shallow coastal waters and busy maritime corridors.

Natural hazards matter too. Underwater landslides can damage multiple lines at once. Earthquakes can rearrange seabed geography. Storms do not “hit” cables deep in the ocean, but they can affect coastal operations and landing infrastructure. This is why networks are designed for redundancy: multiple routes, diverse landings, and traffic engineering that reroutes around failures.

How repairs work (in simple steps)

1) Locate the fault

Operators detect the approximate break location using optical measurements and power/attenuation signatures. The goal is to narrow the search area fast.

2) Dispatch a cable ship

Specialized repair vessels mobilize with grapnels, ROVs, and spare cable segments. Distance, weather, and permitting influence response time.

3) Retrieve and splice

The damaged section is raised, cut, and re-spliced. Fiber splicing is precision work—effectively surgery for glass.

4) Test and re-bury (coasts)

The repaired segment is tested for signal integrity. In high-risk shallow areas, the cable may be buried or protected again to reduce repeat incidents.

The paradox of the modern world: the highest-tech system depends on a repair process that still looks like marine salvage.

Why Satellites Don’t Replace Cables

Coverage ≠ BackboneA common search question is “Why not just use satellites?” The practical answer is tradeoffs. Satellite networks are excellent for remote access, mobility, disaster recovery, and new connectivity options. But backbone economics are brutal: the world pushes enormous amounts of data through a small set of trunk routes. Fiber scales that throughput more efficiently for point-to-point continent links.

Fiber is a capacity engine

For heavy trunk routes, fiber offers extremely high delivered throughput with stable performance profiles.

Physics + routing reality

End-to-end delay depends on route geometry, hops, and network design. Fiber often remains the default for latency-critical flows.

Satellites are strategic backup

Satellites provide alternate paths, especially where terrestrial infrastructure is fragile or absent—complementing the cable backbone.

Summary: satellites expand reach; submarine cables carry the bulk. The modern internet is a hybrid—wired core, wireless edge, and orbit as selective reinforcement.

Decode the Digital Map Under Pressure

Can you identify submarine cables when labels vanish and the map is mixed with shipping routes, air traffic, night lights, and cellular coverage? This is the point of The World Pulse: recognizing system signatures, not memorizing names.

Training benefit: if you can separate “moving goods” from “moving information” visually, you’re building real-world intuition for geopolitics, infrastructure risk, and network resilience.

FAQ + Glossary (Search-Friendly)

High-intent keywordsWhat is a submarine cable?

What is the “internet backbone”?

What is a cable landing station?

Why do cables follow certain routes?

What usually causes cable outages?

- Latency: delay between request and response.

- Bandwidth: maximum throughput capacity.

- Topology: the structure of connections (nodes + links).

- Redundancy: alternate paths that preserve service under failure.

- Chokepoint: constrained corridor with limited alternatives.

- “The cloud is wireless.” It’s mostly fiber, plus wireless at the edge.

- “Satellites carry most traffic.” Satellites help with reach; fiber dominates backbone volume.

- “Cables are safe because they’re deep.” Most damage is near coasts where humans operate.